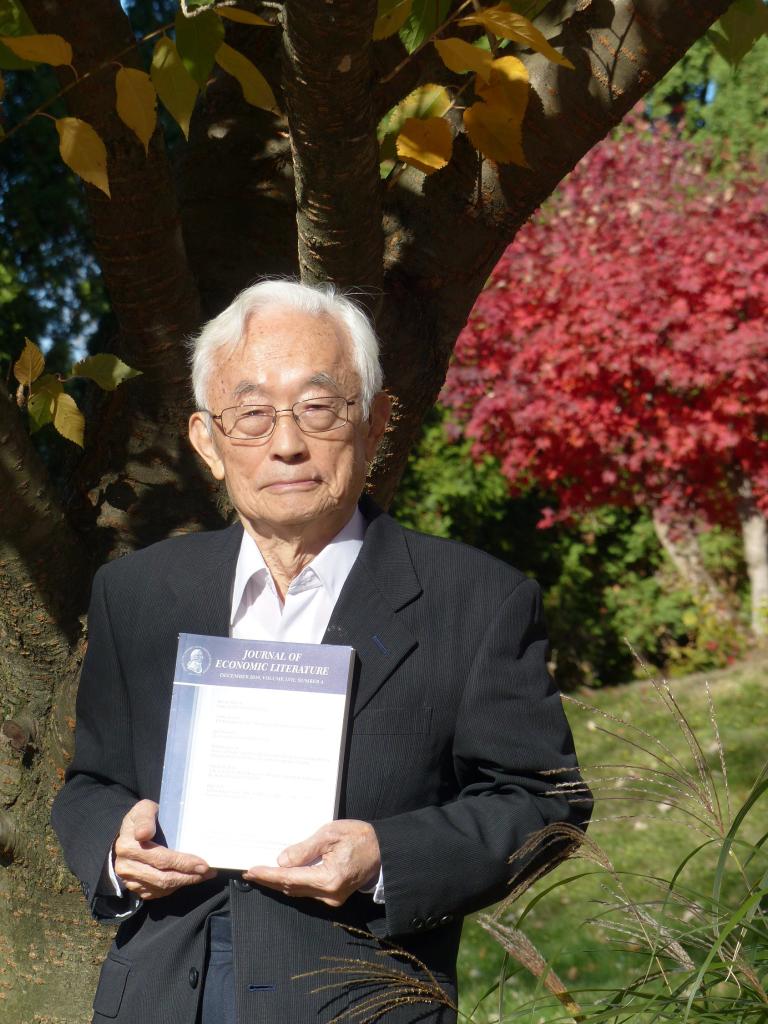

Asatoshi Maeshiro, Faculty Emeritus, was a faculty member in our department for parts of six decades, joining us after earning his PhD from the University of Michigan. He was awarded a lifetime membership in the American Economic Association for his many years of service, and he recently shared his proudest achievements, his memorable moments, and how he has been keeping busy in retirement.

Asatoshi Maeshiro, Faculty Emeritus, was a faculty member in our department for parts of six decades, joining us after earning his PhD from the University of Michigan. He was awarded a lifetime membership in the American Economic Association for his many years of service, and he recently shared his proudest achievements, his memorable moments, and how he has been keeping busy in retirement.

What do you like the most about the field of economics?

I have had the good fortune to study and enjoy a wide range of subjects that comprise economics, so I suppose that the breadth of the field is what I like most. I was interested in development economics as an undergraduate at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo, but my graduate experiences directed my focus to quantitative specialties. At the University of Wisconsin while pursuing a master’s degree, I took econometric and mathematical statistic courses believing that they can be useful for any economic research. At the University of Michigan, where I completed my PhD, I was lucky to be accepted as member of “Research Seminar in Quantitative Economics” where the Michigan model (an extended version of the Kline-Goldberger model) had been used to forecast the US economy. While on faculty at Pitt, I began to serve as a classification and editorial consultant to the Journal of Economic Literature (JEL) beginning in 1970 (a relationship that continued after my retirement). My JEL responsibilities included reading articles in every field of economics and expanded my interest to other fields (e.g., international, comparative, behavioral, and demographic economics), but my research and expertise remained in finite sample econometrics. Incidentally, I was awarded a lifetime membership in the AEA in 2005 for my many years of service as a consultant. As a result, I receive the AER, the JEL, and the JEP every quarter, which I am enjoying during my retirement.

What were your greatest successes in your research career? Any paper or finding you are especially proud of?

I have published many papers in the field of finite sample econometrics, econometrics of AR(1) disturbances in particular. These two papers related to the Cochrane-Orcutt estimator have been cited in most econometric textbooks: “Autoregressive Transformation, Trended Independent Variables and Autocorrelated Disturbance Term” (Review of Economics and Statistics, November 1976) and “On the retention of First Observations in Serial Correlation Adjustment of Regression Models” (International Economic Review, February 1979). As a result, the Cochrane-Orcutt estimator has become less popular among applied econometricians.

The more important finding (for me) is in “Small Sample Properties of Estimators of Distributed -lag Models,” (International Economic Review, November 1980). This paper shows for the first time that the inconsistent OLS can outperform the asymptotically efficient almighty GLS. Unfortunately, the paper has been disregarded by asymptotic econometricians and econometric textbook authors. Perhaps their oversight is because the paper was based on the results of a Monte Carlo study, and its finding challenges the golden rule of asymptotic econometrics that an inconsistent estimator is undesirable or unacceptable, to which econometric textbooks faithfully adhere.

We know why and how the OLS can outperform the GLS. Using a simple stationary dynamic model, my paper “A Lagged Dependent Variable, Autocorrelated Disturbances, and Unit Root Tests-Peculiar OLS Bias Properties-A Pedagogical Note” (Applied Economics 31, 1999) derived mathematically an approximate bias of the OLS that shows why, how, when the OLS can outperform the GLS. The derived function is linear, consisting of two terms, which I named the dynamic effect and the correlation effect. The corresponding relationship for a nonstationary dynamic model with one exogenous variable x(t) was studied by a Monte Carlo method using various ARMA disturbances in “Peculiar Bias Properties of OLS Estimators when Applied to a Dynamic Model with Autocorrelated Disturbances” (Communication in Statistics. 19(4)). A critical finding is that the dynamic effect is affected by the nature of the exogenous variable x(t). The effect is much smaller when x(t) is nontrended than when it is trended (e.g. real GDP). This fact can explain perfectly the seemingly contradicting results of the past related Monte Carlo studies.

My advice to econometricians and textbook authors is “accept the truth related to the estimation of the dynamic model with autocorrelated disturbances and teach it” since we know why, how and when the OLS can outperform the GLS.

Can you tell us about your best memories of research collaboration with another Pitt faculty?

When I joined the department as assistant professor in 1965, the late senior colleague Jacob Cohen asked me to join his research project to study the relationship between the money supply and economic development at the state level. I decided to use two estimators: 1-the Cochrane-Orcutt estimator (at the time, the universally accepted conventional estimator for such a regression model) and 2- OLS because I wanted to know how much better the Cochrane Orcutt estimator is.

When I compared the two estimates side by side for the states, a definitive conclusion followed that the OLS estimates are more reasonable than the Cochrane-Orcutt estimates. The unexpected finding motivated me to initiate research that yielded the two important papers listed above. Had we not pursued this joint project, the Cochrane-Orcutt estimator might have stayed as the common popular estimator among applied econometricians. Our findings were published in “Significance of Money on the State Level,” (Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, November 1977).

What was a satisfying experience you remember having as a teacher?

Learning about the achievements of former undergraduate and graduate students and their positive reflections of our interactions, even years after I taught them or served on their dissertation committee, is a source of great joy. When I joined the department in 1965, I was the only quantitative economist (econometrics and mathematical economics) and was allowed to create 13 new courses, including “Research Seminar in Quantitative Economics” similar to the University of Michigan. I was very happy that the new courses became popular among undergraduates as well as graduates, resulting in an increased number of dissertations using econometric methods.

My students included first-generation college students and non-traditional students who were incarcerated, so I aimed to support them, asserting, “You are much smarter than you think!” and “You can do more than you think!” This encouragement is derived from my own experience as a student at the University of Wisconsin when Professor Goldberger encouraged me to pursue a PhD rather than a Master’s degree. I encouraged students to help one another through my policy of not grading based on a percentage distribution. I also explained to students that the sum of what each of them learns is my source of psychic income, so both the students and I benefit from their studies.

What do you enjoy doing during retirement?

Retirement provided more time for travel, family activities, hobbies, community engagement, and continuing my research interests. My wife and I enjoyed more regular trips to Japan, including visits with relatives and to our ancestors’ gravesites to pay our respects. I taught my grandson arithmetic and helped his baseball and golf practice. He majored in statistics and graduated from college this year. I love nature and endeavor to continue gardening as much as I can.

I had played a leading role in establishing the Japanese Nationality Room in 1999 and am still active in its management. I have also been involved in the Pittsburgh Sakura Project, a nonprofit organization that collaborates with Allegheny County to plant cherry trees in North Park, since its inception in 2009.

I continue my mission to explain why and how the inconsistent OLS can outperform the asymptotically efficient GLS. I have sent e-mails to close to 900 economists and now, I am sending emails to authors of econometric text books with this message. (It is not easy to break the vested interests of asymptotic econometricians.)